To anyone paying attention to the news this past week, the world became a more frightening place. In addition to the brutal massacre by Islamic Extremists at the Charlie Hebdo offices in France, a street magician in Syria was beheaded by ISIS for performing "offensive" magic and the Saudi Arabian blogger Raif Badawdi began receiving the first of his 1000 lashes (50 at a time over a period of months to kick off a 10 year prison sentence) for starting a blog which encouraged free inquiry and women's rights. For freethinking reasonable people, 2015 is not off to the best start.

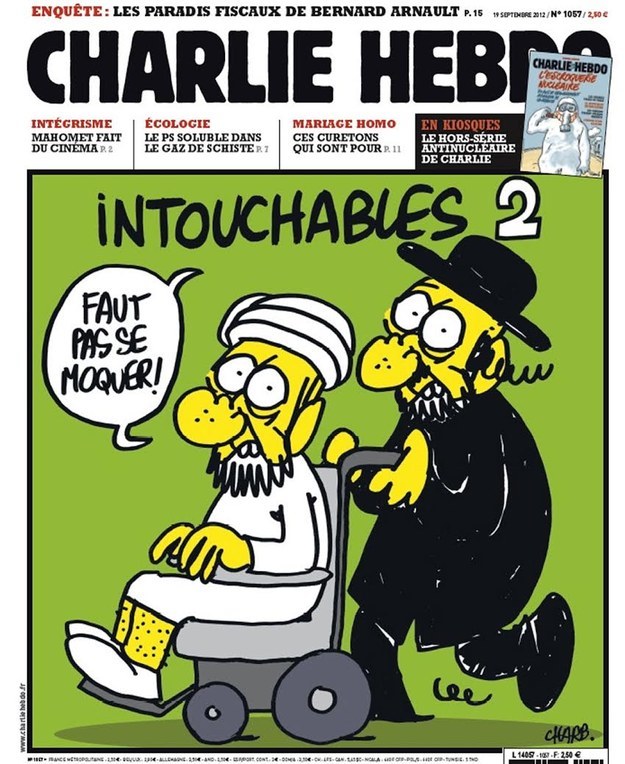

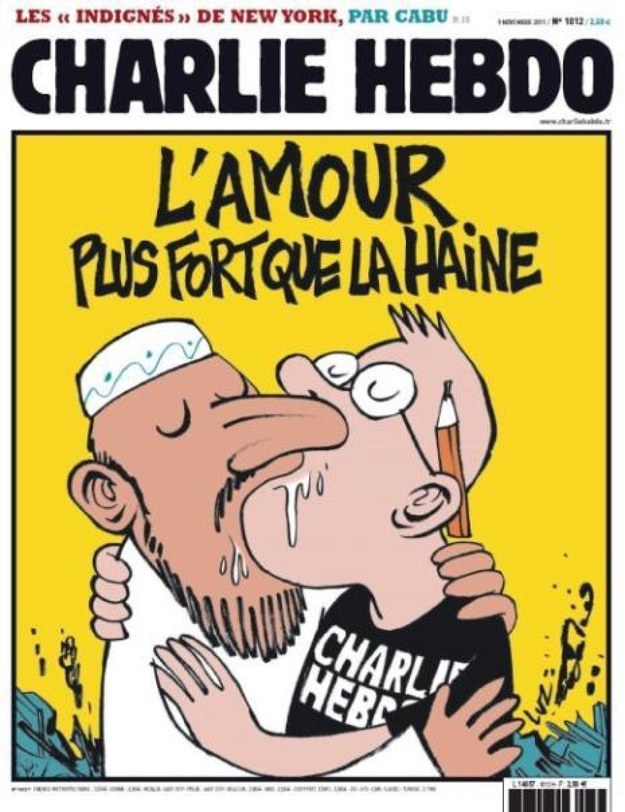

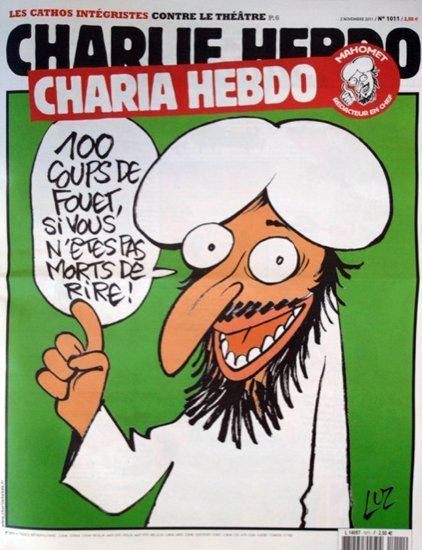

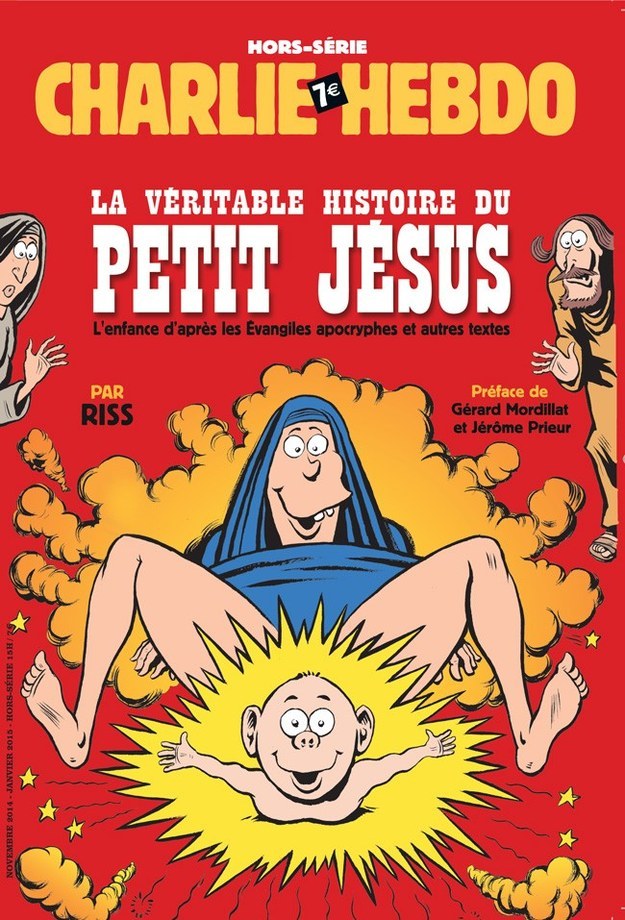

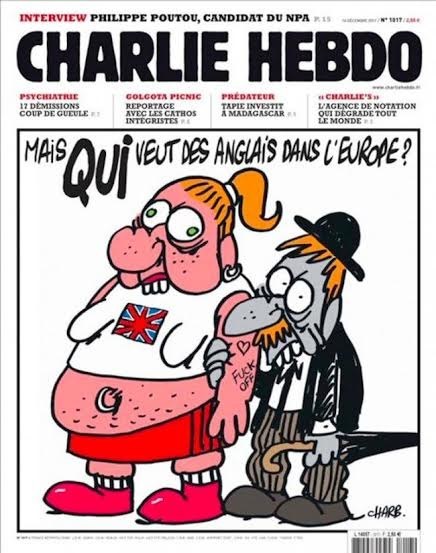

Warming, this post contains images of the allegedly "offensive" Charlie Hebdo cartoons below the fold. They are included in solidarity with those who lost their lives for drawing cartoons and in support of free speech around the world. If you don't want to look at them, you don't have to.

Whether or not anyone is any more or less "safe" than they were before this week of atrocities is debatable. We all fall victim to the availability heuristic where we take things which are top of mind and exaggerate their importance and their regularity. So we feel insecure when images of senseless violence are readily available, even though the actual danger was there all along and went unnoticed. Conversely, we start to feel safer as time passes and the graphic events fade from recent memory. Comes with the territory of owning a human brain.

What makes this set of deplorable events noteworthy is that all three are centred around the imaginary crime of blasphemy. (This is in contrast to the violent actions carried out by groups like Boko Haram whose actions could more reasonably be portrayed as a radical military group that happens to be Islamic.)

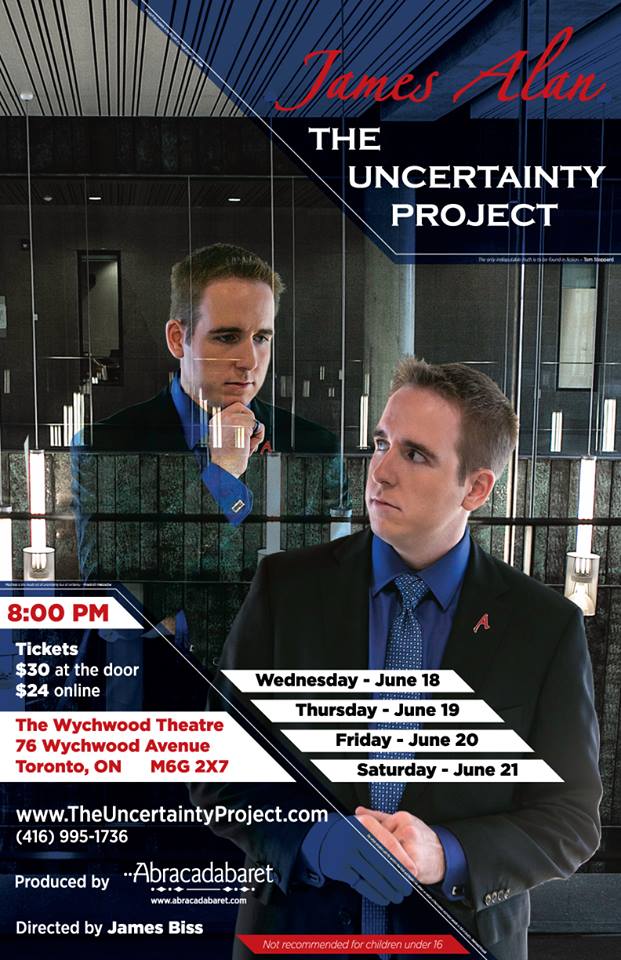

As often happens, I look at many of these events through the lens of magician which offers to important insights. These come from understanding what magic is and how magic is constructed.

When I use the term magic, I'm referring to the kind of magic performed by the unfortunate Syrian victim; the kind which operates by pure human ingenuity and doesn't rely on anything mystical or supernatural. Any appearance of being fantastical or miraculous is simply a misapprehension on the part of the viewer. Many have argued that we should use the term illusion for this type of conjuring to separate it from what we are otherwise forced to call "real magic". I object to this line of thought because that only gives undue legitimacy to people who claim such "magic" actually exists in the real world. If you can perform a trick on the street or at a party, then that magic is very much real and doesn't deserve to take a back seat to fantasy in this way.

Magic is constructed by anticipating (and subsequently exploiting) the perceptions, assumptions and reasoning processes of the audience. The more specifically and more accurately these thoughts can be predicted, the easier it is to fool someone. For example if the objective were to cause a small object like a flower, a finger ring or a coin float in midair. A magician will know that in the mid of an audience, the two most direct ways to make an object rise up are to push it up from below or pull it from above. So if the magician waves his hand above and below the floating object, the viewer will definitely be started and confused. This is because the notion that it's possible to lift something from the side, with a fine thread running parallel to the floor, doesn't naturally occur.

What is magic, then, as I am using the term? It is when an agent (magician) takes an observer (audience) with insufficient information and leads them to an incorrect conclusion about how the world works. That conclusion may simply be agnosticism — I have no idea where that lemon came from — or could be a factual error — he really was floating two feet off the ground. The insufficient information is important. If the audience knew how the trick worked, there wouldn't be a sense of having seen something "magical" (impressive and deserving of respect maybe, but no longer magical). Magic works because the magician has access to information (a principle of physics, the location of an invisible string, a specially trained crew of mice carrying objects up his sleeve) the audience doesn't.

The connection to blasphemy should almost be apparent. We all begin with insufficient information about the universe. Nobody knows with certainty what happens when we die, how the universe began, how the first life on this planet formed or why the laws of physics are the way they are. And in the past, this lack of information has lead people to all kinds of erroneous conclusions about how the world works. This can be from the "turtles all the way down" hypothesis to the inane quantum woo of Deepak Chopra. For billions, it's the religious beliefs of their parents. (Of course, if you are willing to do some research, you'll find we have much better and very reasonable explanations for these things and some rather significant evidence which makes them plausible). In this context, religion itself can be seen as a magic trick a species played on itself.

The people who are motivated to punish blasphemy do so because they are wrong about the way the world works. And whether the cause of their wrongness is childhood religious indoctrination, dishonest apologetics or mental health issues may affect the amount of empathy and compassion we feel for them, but does nothing to reduce their wrongness. As a magician, I take particular offence at those who are so ignorant as to accuse us of being in league with the devil, or being possessed by malevolent spirits. These people need to get themselves into the twentieth century.

When properly expressed, the reasons for prohibiting blasphemy sound idiotic. It's actually a fairly complex proposition: First, it presupposes the existence of an omnipresent deity that watches you and reads your thoughts. On top of that, this deity is so concerned with "proper" thought and conduct that it takes out its anger both in this life and the next. Finally, this deity is so hamfisted, he's incapable of directly punishing the people who misbehave, he takes out his anger randomly. This isn't an exaggeration. There are no shortage of fundamentalist preachers actively declaring floods, hurricanes, droughts, earthquakes and infectious diseases to be consequences of same-sex marriage and and South Park. You would think an omnipotent god could manage a bit more subtlety; a well timed blood clot or a well positioned lightning bolt. That has to be easier to organize than an entire ebola outbreak.

This is, of course, all a delusion. In the real world, blasphemy has the same physical effectiveness as a child pointing a toy ray gun at you and making pew pew sound effects, or pointing a stick at you and shouting "Avada Kedavra". It doesn't do anything except send some sound waves propagating through the air. The same is true of "offensive" cartoons and irreverent books. But if you take blasphemy seriously, you think that they have the power to actually turn the whole universe against you. It would be like arresting someone for trying to force choke their sibling from across the dinner table.

The unpleasant logical consequence of this is that if I can be punished for your blasphemy, then I'm obligated to actively dissuade you from blaspheming. Add in something about earning god's forgiveness and you wind up with a corollary that you also need to punish blasphemers. This is transparent superstition that the civilized world cannot afford to take seriously. We need to remember that the religious freedom for the individual does not entitle them to dictate behaviour for everyone else.

#JeSuisCharlie